Roger Hilton (2)

Introduction by Michael Canney to the first edition of “Roger Hilton: Night Letters and Selected Drawings”, 1981

The decision to publish a selection of the so-called “Night Letters” of Roger Hilton has exercised the mind of the artist’s wife ever since his death in 1975. It seemed originally that these personal and at times distressing documents should be accessible only to the family and close friends of the artist. Recently however, it has become apparent that the letters form an essential part of the documentation of Hilton’s life, recording as they do the physical decline of this uniquely creative man. In view of this, and of a growing interest on the part of many who have seen his letters for the first time, it was felt that they should now be published.

Regrettably, some of the most perceptive and entertaining letters refer in highly uncomplimentary terms to persons still living, and these have therefore had to be withheld from publication. The total number of Hilton’s writings is considerable, but even this small selection gives a vivid picture of the artist using his sense of humour and his art to blot out or combat persistent ill-health and the destructive effects of alcoholism. The letters may also give some indication of the motivation behind his sporadic displays of outrageous behaviour that enlivened the British art scene in the 1960s. Those who were his victims may be surprised, or mollified to discover in the letters a man who, despite his dogmatic and arrogant manner was subject to profound doubts, and even regrets.

A selection of Hilton’s later drawings complement the letters. They help to illustrate the intense creativity of his final years during which drawings and gouaches poured in profusion from his bedroom studio. A comprehensive book on the gouaches is long overdue, but in the interim it is hoped that the more modest Night Letters and Selected Drawings will provide a background to the artist’s later work.

In 1974, Roger Hilton, who was by then permanently confined to his bed as an invalid, dispatched a twenty-page letter to the editor of Studio International. Part manifesto and part biography, it made it clear that for him art and life were inseparable: “The tendrils in the art vine are infinite” he wrote. “At the bottom of it all is the poor artist who tries to keep some probity, malgré tout. Because he has all the usual things to cope with, he is not in an ivory tower –electrical appliances, cats drinking his paint water, and so on”. This bizarre conjunction of afflictions is typical of Hilton’s letters; the writing is extraordinarily direct, vividly reflecting his changing moods which run the gamut from resignation to frustration, and indignation to outright defiance. He was in fact, a man who had little patience with ordinary day-to-day problems. Again and again in the letters, complaints and specific wants are painstakingly listed, so many that a number would inevitably be overlooked or forgotten. As a result the “Night Letters” often imply that everything and everyone is conspiring to prevent him working. The closest and most obvious target is usually his wife. It is possible to take these torrents of abuse literally, but his “male chauvinist” attitude in the letters is more of a pose than a reality.

It was true that he could be extremely demanding with women, but he was not particularly possessive. Instead he acknowledged his dependence upon them, enjoyed their company, and spent much of his time celebrating the sensuality and beauty of the female body in his art. Indeed, few artists since the war have been as responsive to the nude as Hilton. Stylistically, Hilton’s drawings of the nude often recall Rodin and Matisse, both of whom he admired, and also Laurens, an artist whom he thought unjustly neglected: “Put into the back seats yet he shines like a beacon” he writes of Laurens – although it seems that in a list of his favourite artists he did not mention him as a major stylistic influence.

The spontaneity of these late drawings is perhaps their most immediately engaging quality, and this spontaneity seems to relate directly to principles that he enunciated in connection with his gouaches of the same period, namely: “Never rub out or attempt to erase; work round it if you have made a mistake. Make of your mistakes a strength rather than a weakness. As in life, it is not what you put in, but what you leave out that counts. Most pictures can be pulled round. If you run into head-winds, tear it up”.

Hilton’s ability to treat the sheet of paper and the drawing as an entity means that the drawings are eminently decorative in the best sense of that word. This is also true of the “Night Letters”, with their happy combination of writing and drawing recalling the great tradition of French illustrated books before the Second World War, or certain etchings by Picasso in which calligraphy is combined with lively marginal illustrations. Hilton’s successive periods in Paris –nearly two years in all between 1931 and 1938 – mark him as perhaps the most French of post-war British artists. His love of France is clearly present in the letters, some of which are in fact written in French. Not only did he enjoy using the French language, but he showed an obvious affection for French cuisine, for French literature, and for the traditional friendship between poets and painters in that country, witness his long association with the poet W. S. Graham, whose tribute to Hilton appears at the end of this book.

He also felt a certain nostalgia for the French ateliers such as the Academie Ranson where he had studied, with its rules of painterly conduct which he would quote with approbation: “When you change the colour change the tone. . . If your drawing is bad, don’t hope to get it better by painting. . . Don’t try to make a ’successful’ drawing or painting. Seek to learn something. . . Command your canvas, never obey it” and so on, dicta of his old master Roger Bissière.

Hilton never believed that there were any short cuts in art. For him a work could only be endowed with spontaneity and life if the artist had first of all mastered his technique through long years of apprenticeship. He devotes a number a pages to this in his collected writings, and his advice is as conventional as that of Cézanne in the famous and much-quoted letter to Emile Bernard: ”Treat nature by the cylinder, the sphere, the cone, everything in proper perspective”. Hilton, for his part writes: “Art results from the long battle and reconciliation of two sovereignties, the idea breathing life into technique, and technique giving idea the fleshly form. . . Most pictures have not enough technique and not enough idea. If l were asked what a person should have first, I would say technique”. And then, as if to expand this unexpectedly traditional view from an avant-garde painter he adds: “In the last resort I am arguing in favour of the sinking of technique to a level of consciousness where it can confront Man, I argue for art as revealed truth, not as significant form, and technique as the instrument of its exposition”.

In later years Hilton placed vitality and feeling above all else, but the vitality of his own line and the spontaneity of his gouaches owes much to his mastery of technique acquired during his apprenticeship at the Slade, in Paris, and during his austere abstract period of the early 1950s. It must be added, that the apparent ease of his drawings, and the shaky and searching line, make him a dangerous master. A note in his collected writings indicates that he was aware of the intensely personal nature of his own drawings: “As you live it changes the line you make” he writes. “As your life is, so is your line. As you live it becomes more your line. The line says more. . . at first you make many lines, and then you only have to make a few, and they say more”.

In Hilton’s best drawings it is impossible not to empathise with the rhythmic undulation of the outline and the frankly erotic poses of his nudes. The contained shapes of his figures and the containing shape of the paper on which they are drawn, are locked together in a unified image, so that not only the line but the paper itself shimmers with an inner life. The expansive quality of the drawing recalls, in an oblique way, his early interest in the expansive potential of form and colour in painting. He writes of these early abstract paintings, “They have the effect of projecting space back into the room. The advantage is that instead of space being empty it is filled. The colour and forms of the painting penetrate the surrounding space imparting to it their vibrations. It is a case of equalising external and internal pressures”. This is certainly relevant to the drawings, which possess an ability to generate pressure within the forms and across the surface, so that the margins of the page seem barely able to contain them.

The individuality present in the drawings is present in Hilton’s letters as well, even in their calligraphy which becomes more and more like his drawing as death approaches. Tinged with an Existentialist mood that derives from his days in Paris, it is clear in his more desperate letters that the struggle for existence and the revelation of a durable truth is what finally counts. “Art if it is anything, is a blood and death battle, into which you throw everything you’ve got”, he writes. “It is dangerous for artists to write or speak about what they do”. If latterly he ignored his own advice, those who knew him when he was young recall a private person who said little; he could, however, fix the unwary with a disconcerting look through his thin spectacles.

Whether is was the result of moderate success after years of obscurity or an increasing addiction to alcohol – a problem that he could never fully explain – sometime in the mid-fifties his character underwent a change. Although he had always possessed great charm and a sense of humour, he now became dogmatic and cantankerous and was subject to abrupt and violent changes of mood. Moreover, he developed an alarming tendency to probe the most vulnerable areas of a person’s psyche. He was it seemed, endeavouring to pursue truth not only in art but in his personal relationships as well, stripping away the conventions of everyday behaviour in order to confront the subject with his or her inner self. When this amateur psycho-analysis took place in public, the resentment of his victims sometimes led to physical attacks on the artist but he still persisted. As a thorn in the body of the establishment Hilton often punctured those who richly deserved puncturing, but latterly his aim became wilder.

It might be thought that his paintings and drawings would give some indication of this destructive side of his personality, but they give none. His art can appear anarchic or undisciplined at times, but it is an optimistic and generous art, sensual and sometimes comic, but never cruel. Although he was working seriously and consistently throughout the sixties striving to achieve a rapprochement between abstraction and figuration, the downhill trend in his drinking continued. In 1966, after a series of drunken driving charges, he was committed to Exeter gaol for examination. The effect was salutary and instantaneous. Incarceration was in itself a shock, but in some respects not as bad as he had feared: “This is much like a P.O.W. camp,” he writes to his wife, “more agreeable in some ways and less in others” – there is a reference here to the three years that he spent as a prisoner of war following his capture in the Allied Commando raid on Dieppe in 1942.

At Exeter it was realised that he was in need of medical help, and he was conditionally released after only six weeks so that he could undergo treatment at St. Lawrence’s Hospital, Bodmin. The cure there was temporarily effective, but two years later the old pattern had re- established itself and he decided to seek treatment at a private clinic in London. The letters that follow his admission there show a remarkable and almost immediate return to normality. This sharpening of his acute powers of perception once again meant unfortunately that he became unduly sensitive to his surroundings and to the abnormality of some of his fellow patients. Life at the clinic became oppressive and deadening rather than helpful. Originally he had intended to stay for six months, but he discharged himself after only twelve weeks and returned once more to his cottage in west Cornwall. A year later his friends and family were dismayed to see that he was drinking heavily once again.

Hilton’s career had begun to parallel the lives of those French writers and artists, often referred to in his letters, who despite drink or drugs devoted their remaining years to an increasingly intensive pursuit of their art. His health was now deteriorating; he could only walk with difficulty and by the end of 1972 he was so enfeebled that he took to his bed for good. He was suffering not only from peripheral neuritis, but also from an irritating skin condition that had in fact dogged him for years. However, despite this steady physical decline his work became increasingly colourful and light-hearted. It was as he said, the only thing left to him.

The cottage on Botallack Moor where he lived was in an area much despoiled by centuries of mining activity. The bedroom was on the ground floor, with a door leading directly into a field that served as a small garden. He disliked views as such, and there was certainly little to see from the cottage, although at the end of the lane was a dramatic coastline fringed by the ruins of old tin and copper mines. Having accepted his bedridden condition, Hilton now established an individual routine that enabled him to work consistently during his remaining years and until a few days before his death. The bedroom became his studio so that he could work whenever he felt inclined, whether this was in the daytime or indeed in the middle of the night.

The room presented a picture of extraordinary squalor. It was as many observed, reminiscent of a scene from Beckett, with Hilton conversing from his bed in a dry and pedantic voice. His conversation when he was in good form was humorous and engaging, punctuated now and then by his abrupt and characteristic laugh. Surrounding his bed was a bewildering collection of multi-coloured jars of gouache paints, books, discarded plates of dried food, the obligatory bottle of whisky together with milk bottles of water to dilute it in a yellowed plastic glass, letters, bills, cigarette packets, and a much abused transistor radio. His painting and writing was done on a low table beside the bed. Originally left-handed he worked leaning on one elbow. This, however, became so sore and inflamed that he had to teach himself to use his right hand as well. He observed, characteristically, that this had actually proved beneficial to his art for he had become too accomplished in the use of his left hand.

Part of Hilton’s charm lay in his ability to entertain, although he seldom indulged in a monologue, for he enjoyed the cut and thrust of discussion and argument too much. As a result an oddly assorted collection of friends, acquaintances, and anonymous passers-by could be found at his bedside when he was not working, poets and writers, artists, actors, students, members of the art establishment and collectors, fashion models, local farmers, and on one occasion a distinguished ambassador. His condition was distressing but there were still moments of high comedy. A friend’s donkey, brought into the bedroom to visit, discovered a collection a cigarette ends and refused to leave: “You’re an amusing animal” remarked Hilton smacking him on the nose, “You’re more intelligent than most of my visitors!” There were, however, periods when he felt neglected, in winter especially when his human contacts were largely confined to Rosemary his wife, and his children, Bo and Fergus. There were animal companions and these kept him company; a black and tousled dog with hazel eyes, a whippet, and a cat that maddened him, but they still could not alleviate the depression of a Cornish winter.

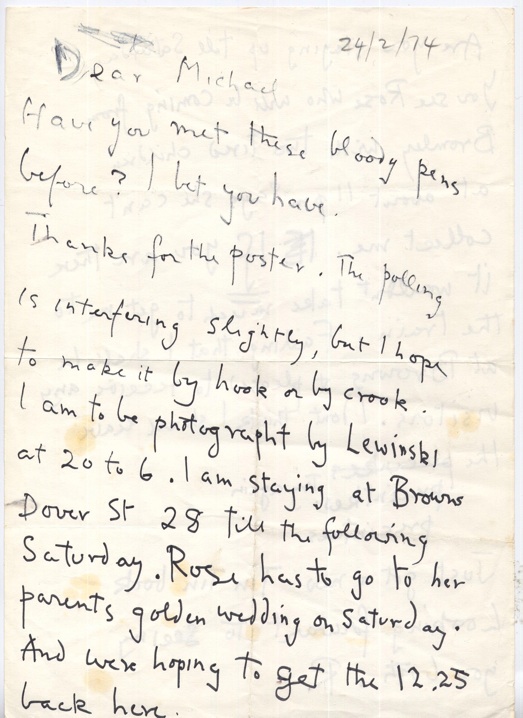

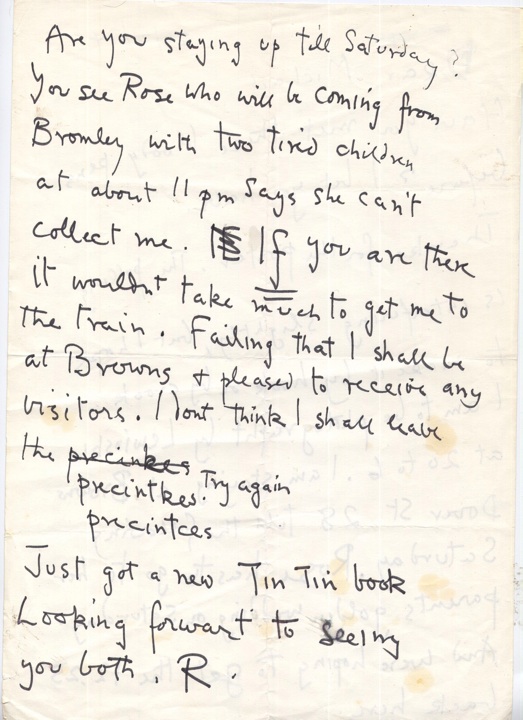

It was during the long night hours that he composed the “Night Letters” to his wife and occasionally to his friends. He wrote, as he himself remarked, because he enjoyed it and because it was something to do between pictures. As his health deteriorated his spelling became increasingly eccentric and the calligraphy shakier, sometimes disintegrating altogether into an indecipherable scrawl. When the family arose in the morning the artist was already asleep, the latest “Night Letters” lying on the table, instructions, complaints, advice, thoughts on life and art. Many reflect a longing for culinary delicacies, recalling the days in Paris, but these were often foodstuffs that were unobtainable in west Cornwall, or impossibly expensive, or if provided were too much for his weakened constitution.

Despite his condition, he possessed hidden reserves of energy, and he was therefore not an easy patient. Certain ideas obsessed him, in particular the tyranny of everyday objects; pens refused to draw, radio sets faded, cats ate his food, envelopes were the wrong size, paints the wrong colour, his stove kept going out, and the ringing telephone was always beyond his reach. On one occasion his stove caught the bedclothes alight, and then the room itself. It was only the prompt arrival of the local fire-brigade that saved the entire cottage and his work from destruction. Occasionally he would accompany his wife to Penzance where he would sit in an antique dealer’s whilst she shopped, but these trips became less frequent as he grew weaker.

By the spring of 1973 Hilton had completed a substantial number of his new gouaches and was anxious to show them, but there seemed to be little interest. He became convinced that he was being neglected, although this was not strictly true, for a London retrospective was already under discussion. However, it was a fact that his work was not selling and that he was financially at a very low ebb. He was therefore much encouraged when in June, the small Orion Gallery in Penzance took the initiative and staged a successful exhibition of his new gouaches. The enthusiasm of visitors and friends raised his morale and the sale of two-thirds of the paintings helped him financially; moreover, the new gouaches were seen to represent a significant stage in his development.

In March 1974 a major retrospective of Hilton’s work was mounted at the Serpentine Gallery in London’s Kensington Gardens – a happy event – the gallery being ideally suited to the work. After much planning and fussing, Hilton made the journey from Cornwall to London for the private view; it was a triumphant occasion. The artist, frail and emaciated, sat clasping his whisky bottle beneath “Oi-Oi-Oi”, one of his most exhilarating paintings, whilst a constant stream of friends and well-wishers came forward to congratulate him. But his condition gave cause for great concern. Steps had already been taken to persuade him to enter Maudsley Hospital for urgent treatment, and it seemed that he might actually agree. Detailed plans were drawn up, but in June he suddenly withdrew his agreement at the last minute and dispatched a lengthy “round-robin” to friends and relatives who had been trying to help him. He was determined to end his life in his own way, and in his own bed.

This defiant mood continued throughout the summer of 1974. In August of that year he decided that the time had come to pay a last visit to France. With an advance of a thousand pounds from his dealer, he made all the necessary arrangements in a matter of hours for a small private plane to fly him, Rosemary, Bo and Fergus, south to Antibes. A few miles from his cottage was the local airport at St. Just, a small field that normally serves the tourist trade as a base for short flights around the Cornish coast. It was from here that a small Piper Apache set off on a seven hour flight to Cannes with the Hilton family on board. The artist was initially in high spirits, and to the pilot’s concern endeavoured to take over the controls, but by the time that they reached Cannes he was fractious, cold, and exhausted.

Once established in Antibes Hilton soon recovered and started work immediately on a new series of gouaches filled with sailing boats, strange seabirds and sun-worshippers. He was aware that there was little time left to him, and his work routine was therefore as regular as if he had still been at home in Cornwall. For relaxation he was taken to a small cafe nearby; it was full of mariners and much to his liking. There he could be left in safety, watching the constant procession of holidaymakers, drinking and chatting with the habitués, finally to be trundled home in his wheelchair by one of his new acquaintances. An additional pleasure in Antibes was a small circus where he would remain for hours, delighted by its cheerful ambiance and by the performing animals. Some of his earliest drawings had been of circus animals, camels for which he had a particular penchant, Palomino ponies, and elephants too, a recurring subject even in some of his near abstractions.

The visit to Antibes was therefore a success, but it was to be the last time that he would be able to leave his bed. Six months later he suffered a brief stroke and died. He was buried in a bleak cemetery on Carn Bosavern high above St. Just and overlooking the Atlantic; the headstone to his grave was a granite boulder from his own garden. After his death and underneath the bed was found a final and apparently solemn “Night Letter” – it reads: “Yea though I pass through the valley of death, I fear no evil. Thy rod and thy staff shall comfort me”; but with a typically abrupt change of mood he introduces a gaily spotted snake, zig-zagging across the middle of the page. Some have seen in it a self-portrait, others a reference to the Garden of Eden; perhaps it is the latter, for below is a buxom nude with upturned nipple, and a childhood riddle that he leaves incomplete: “Adam and Eve and Pinch-me went down to the river to bathe. . . ”